On Tuesday, Kamala Harris delivered the performance of her political life, schooling Donald Trump before 67 million viewers. To top it off, she garnered the endorsement of Pennsylvania native Taylor Swift and swung the prediction markets her way. Still, the Harris-Walz campaign is just breaking even in Swift’s home state—and only narrowly ahead in Michigan and Wisconsin. Democrats trail badly among voters without a four-year degree. A replay of 2020 looms.

In hindsight, Harris’ selection of Tim Walz as VP may yet prove costly, even outcome determinative. In early August, she could have gone a long way to locking down the Keystone State and its 19 electoral votes, had she picked its governor, Josh Shapiro. Instead, the vice-president went with someone who wouldn’t outshine her. (Some contend that Harris was scared-off of Shapiro by her party’s progressive-wing.)

Confident politicians recognize that boldness can yield outsized rewards. John F. Kennedy in 1960 and Ronald Reagan, 20 years later, discounted “chemistry” and opted for their rival. Both knew that only thing mattered—winning.

Kennedy forged a Boston-Austin axis when he went with Lyndon B. Johnson, even after LBJ had challenged him for the nomination and dominated the Senate. Reagan selected George H.W. Bush, an ex-CIA director and congressman who had notched a string of victories during the GOP presidential primaries—and repeatedly stung Reagan with the phrase “voodoo economics.”

Pragmatism ruled; interest groups, not necessarily.

“Senator Kennedy overrode protests by labor and Northern liberals in the surprise move in naming the Senate majority leader for Vice President,” the New York Times reported back in day of LBJ joining the Democratic ticket. “Kennedy, a Roman Catholic, moved boldly to win party unity and new strength below the Mason-Dixon Line by choosing the Texan, a Protestant, for his running mate.”

The gambit paid-off. Johnson’s presence put enough Texans at ease that, on Election Day, the Democrats narrowly carried the state and its 24 electoral votes. Four years earlier, Texas had gone Republican by double-digits; nationally, Kennedy’s margin over Richard Nixon was an infinitesimal one-sixth of one percent.

Two decades later, history repeated itself. Reagan tapped Bush for a team that was a study in contradictions. More importantly, it worked.

Sure, the Sunbelt-minded ideological right never cottoned to the Yale Skull and Bonesman. But once in office, Reagan made the most of Bush—or at least his talent. He layered his administration with Bush campaign veterans. James Baker, Bush’s campaign chairman, emerged as Reagan’s first White House chief of staff. Many other top appointees—including Richard Darman, a Baker deputy and Harvard alum—were more Bush Establishment than Reagan Revolutionary.

Back to the present. Walz puts a smile on the face of the Democratic base but few others. He is likeable and familiar, yet questions about his military service undercut possible broader appeal. These are nuances that Team Harris, more attuned to the vagaries of political correctness than military folkways, perhaps failed to appreciate during the vetting process.

Unlike J.D. Vance, Walz does normal. He doesn’t trash single women, harangue the childless or parrot Kremlin-issued talking-points about Ukraine. He also doesn’t defend Tucker Carlson. At the same time, however, his victory in the veepstakes reinforced the perception that Harris is incapable of bridging America’s culture and demographic gaps.

In his home state of Minnesota, Walz has shown little strength beyond traditional Democratic turf. He won reelection in 2022 by a smaller margin than he had in 2018. Indeed, his totals were in line with Joe Biden’s performance in 2020.

By contrast, in 2022 Pennsylvanians elected Shapiro governor by double-digits, 56-42. And Pennsylvania is the swingiest of swing states.

The polls signal other difficulties for Harris. “Another warning sign for Democrats,” according to a New York Times/Siena poll published on September 8, “47 percent of likely voters viewed Ms. Harris as too liberal, compared with 32 percent who saw Mr. Trump as too conservative.” To put that another way, by a 15-point margin, Americans see Harris as further from the political middle than Trump. In that sense, Walz reminds voters of Harris’ difficulty in tacking to the center.

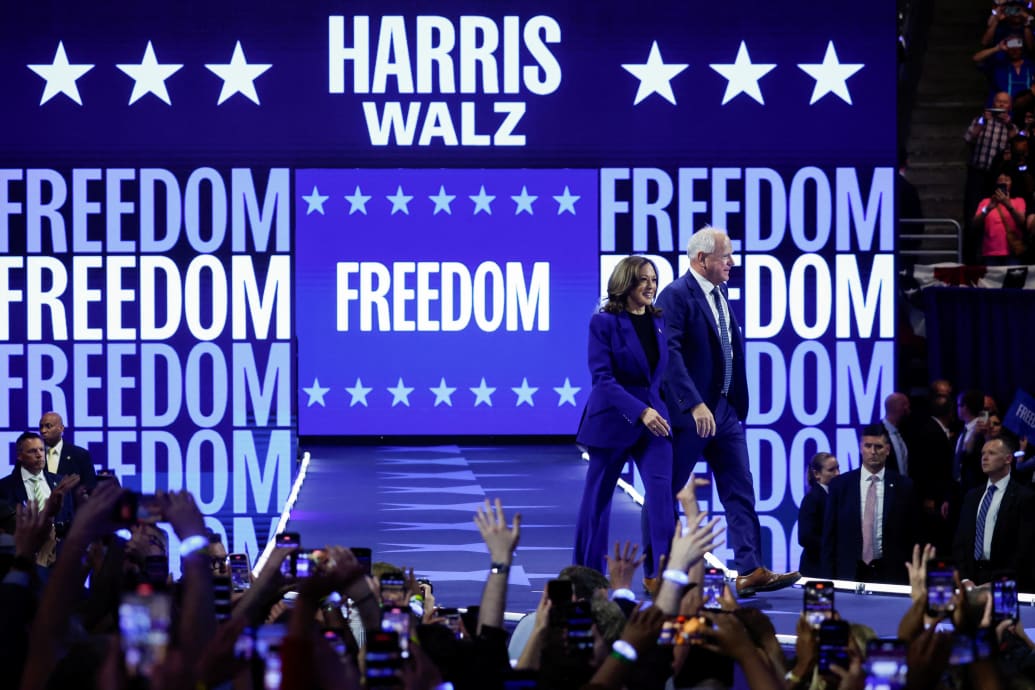

Democratic presidential candidate Kamala Harris and her running mate, Minnesota Governor Tim Walz, attend a campaign rally in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on August 20, 2024.

Marco Bello/REUTERS

Recent endorsements by Liz and Dick Cheney speak to the threat the 45th president poses to U.S. democracy, a major concern of the high-end. But to a sizable mass of voters, Harris needs to grapple with a broader range of issues. Tuesday was a start.

In the run-up to the debate in Philadelphia, Team Harris had camped out in Pittsburgh. Once on stage, Harris framed her positions with an eye toward Pennsylvania. She expressly reminded the state’s 800,000 Polish-Americans of the threat Vladimir Putin poses to their ancestral homeland.

Harris also reiterated her opposition to a fracking ban with the state on her mind. “Let’s talk about fracking because we’re here in Pennsylvania,” she said at another point. “I made that very clear in 2020. I will not ban fracking.”

“Pennsylvania is Philadelphia and Pittsburgh with Alabama in between,” James Carville, Bill Clinton’s campaign guru, wisecracked in 1991. Had Gov. Shapiro been on the ticket, navigating that terrain would be that much easier.

![Tyson Foods Plant [Photo: Food Manufacturing]](https://southarkansassun.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/iStock_1185520857__1_.5e441daa51cca-600x337.jpg)

![Silverado Senior Living Management Inc. [Photo: Los Angeles Times]](https://southarkansassun.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/download-6-4-600x337.jpg)

![China's Wuhan Institute of Virology [Photo: Nature]](https://southarkansassun.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/d41586-021-01529-3_19239608-600x337.jpg)