Animation maestro Hayao Miyazaki has given the world a lifetime of joy and entertainment via his Studio Ghibli films.

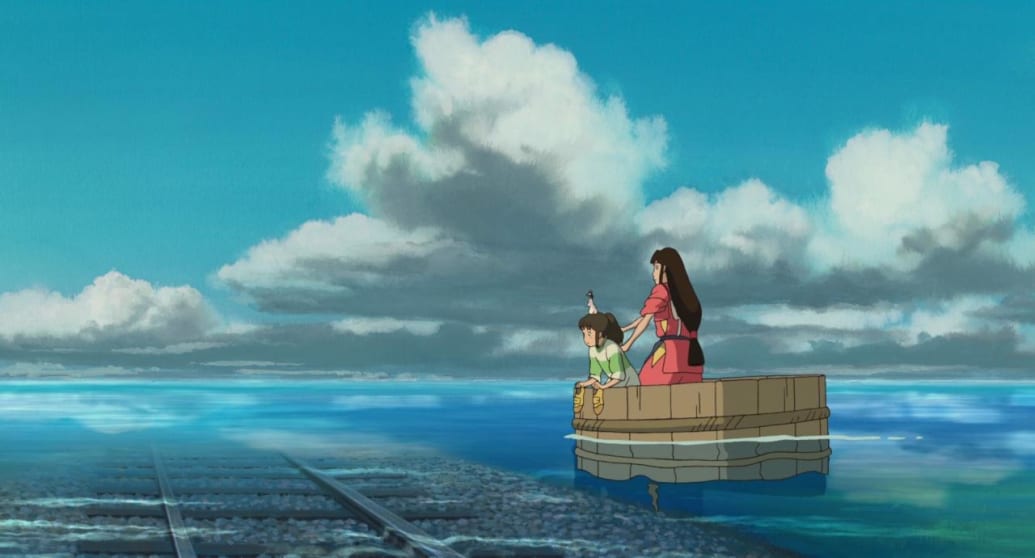

Miyazaki is behind some of the most beloved films of the last 40 years, including My Neighbor Totoro (1988), Spirited Away (2001), and Ponyo (2008). A new documentary by Léo Favier, Miyazaki, Spirit of Nature, explores the director’s challenging rise to the top of the animation, arguing that his films are best appreciated in an environmental context—Miyazaki’s boundless passion for nature and his relationship with the world around him is crucial to appreciating his work.

Miyazaki, Spirit of Nature, which just premiered at the Venice Film Festival, has three intertwining narrative threads—an exploration of the state of the world, a timeline of Miyazaki’s life, and the films Miyazaki directed. Favier is a passionate advocate for Miyazaki’s films, and the viewer always has a clear idea of what Miyazaki and the world was going through when each of the films featured in Spirit of Nature were being made.

Oddly, though Miyazaki has directed 12 films (a large number by animation standards), not all of them receive attention here. Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989) is glossed over almost entirely, Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) gets a couple of brief clips, and The Wind Rises (2013) is mentioned only by name.

These are strange omissions, as these three films are relevant to Favier’s discussion of Miyazaki’s passion for nature. The Wind Rises, about the creation of Japanese fighter planes, is practically begging for Favier’s thoughtful and detailed analyses, and I’m sure the numerous experts the director interviews, including Miyazaki expert Susan Napier, son Goro Miyazaki, or producer Toshio Suzuki, would have compelling insights into the film. The simplest reason not to focus on a feature in someone’s oeuvre is that it doesn’t fit your argument, but all these movies would have strengthened Spirit of Nature’s insights, not weakened them.

The oddest choice is the last-second introduction of Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron. The enormously successful Ghibli movie was Miyazaki’s return to filmmaking after promising retirement, earning him a second Academy Award. It’s a culmination of everything in Miyazaki’s career and is a particularly bold exploration of nature and our relationship with the world. Yet Spirit of Nature quickly tacks on a discussion of The Boy and the Heron in the final seconds. While Favier touches on how the film fits into Miyazaki’s lifelong relationship with the environment, it’s disappointing to see the discussion be so rushed. Perhaps the hurried nature of the segment is because the film was already finished when Boy and the Heron came out, but it feels like a considerable omission to give such a major work minor time.

Despite these choices, Spirit of Nature is still a warm, insightful celebration of one of the most influential filmmakers in the history of animation. Favier’s film is a critical analysis of what makes his work so admirable and essential. Though Miyazaki himself was not interviewed for the film (he’s famously uninterested in being interviewed), Spirit of Nature includes plenty of archive clips of the master at work, drawing away in the humble corner of his office that he shares with others. Most excitingly, Favier has gained access to Miyazaki’s film excerpts, which Favier shares with beautifully composed images of real nature, delivering first-person insight into what precisely Miyazaki was feeling and thinking when he made many of his greatest films.

Just as Miyazaki’s films refuse to pander to children, thriving on complex ideas, Favier’s film draws in intellectual thinkers like anthropologist Philippe Descola and writer Natsuki Ikezawa. They illuminate concepts like animism—Favier does great work binding their words to key images from Miyazaki’s films, highlighting how these beliefs are an important step to understanding the dazzling creatures Miyazaki has created.

While the film doesn’t explore the complexities of animation as a medium, it thoroughly investigates the Japanese filmmaker’s relationship to nature, clearly clarifying how Miyazaki, Spirit of Nature promises plenty of rewards for those who watch it—most of whom, I suspect, will be ardent fans of Studio Ghibli. There’s plenty of compelling information, like how Porco Rosso (1992) drastically changed the scope and direction in the creative process. Or how the first animated film Miyazaki saw—The White Snake Enchantress (1958)—changed his life. Even those who’ve seen every Miyazaki film many times will find exciting new insights here.

Favier’s adoration of Miyazaki is evident in every frame, and the experts Favier has assembled—including his son, filmmaker Goro Miyazaki—have nothing on the utmost respect for him, too. It manages to avoid being hagiographic by exploring the darker elements of Miyazaki’s life. Spirit of Nature offers a tantalizing portrait of a filmmaker often at war with himself, a man with an undying love for the environment around him mired in increasing despair at the state of the world.

![Tyson Foods Plant [Photo: Food Manufacturing]](https://southarkansassun.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/iStock_1185520857__1_.5e441daa51cca-600x337.jpg)

![Silverado Senior Living Management Inc. [Photo: Los Angeles Times]](https://southarkansassun.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/download-6-4-600x337.jpg)

![China's Wuhan Institute of Virology [Photo: Nature]](https://southarkansassun.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/d41586-021-01529-3_19239608-600x337.jpg)